(This week marks the 30th anniversary of Die Hard, arguably the greatest action movie of all time. To celebrate, /Film is exploring the film from every angle with a series of articles. Today: the cast and crew look back on the making of an action classic.)

John McTiernan‘s 1988 action tour de force is one of my favorite movies ever made. It’s a masterclass on every level: building entertaining characters, crafting escalating action, establishing and navigating geography, and putting an empathetic hero through the ringer in the face of extraordinary odds. McTiernan and his collaborators made this all look easy, but as the rash of Hollywood imitators that followed quickly proved, it was anything but.

Die Hard turns 30 years old this weekend, and to celebrate, I spoke with cinematographer Jan de Bont, writer Steven E. de Souza, and actor Reginald VelJohnson (who played Sergeant Al Powell) about why the film still holds up, how some of its most memorable scenes came together, and much more.

As originally envisioned, this piece would have featured quotes and anecdotes from one person seamlessly flowing into stories and recollections from the next, sort of like the oral history format I used when I wrote about the incredible throne room lightsaber fight scene in Star Wars: The Last Jedi. But each of the participants in these Die Hard interviews were so gracious with their time and had so many distinct stories to tell that it would have done them a disservice to blend them all together. So instead, I’m going to present the highlights from my conversations with each person one at a time.

Note: These interviews have all been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

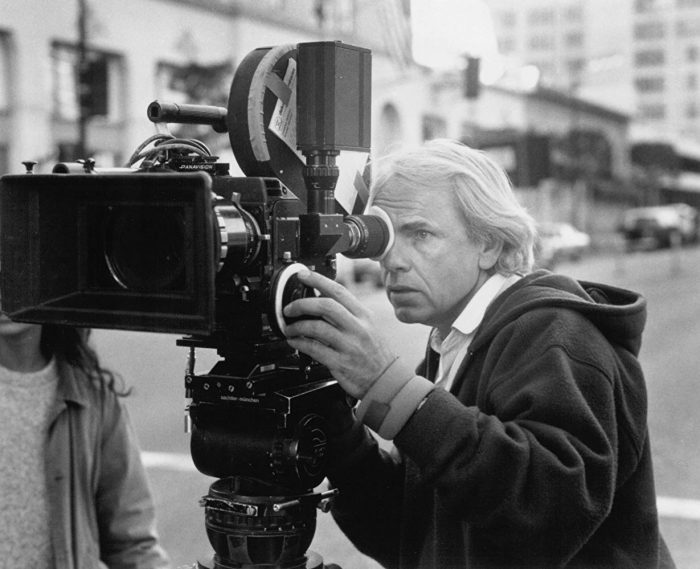

Jan de Bont Die Hard Interview

First up, here’s my chat with cinematographer Jan de Bont. De Bont went on to become a notable director in his own right with films like Speed and Twister, but was a key part of crafting the look of McTiernan’s classic. He told me about how he made an office building look cinematic, the power of shooting real explosions, and how the production used experimental military technology to film one of the movie’s most iconic shots.

/Film: Before you started production, did you take a look at any other films or have any visual inspirations for the movie?

Jan de Bont: Basically, it always comes down to the screenplay. Of course, I was a fan of American movies, and especially like the more realistic type of action movies, and Die Hard – the script itself – was something that I thought, the moment I read it, I could create a visual style that would be really perfect for the time. Where everything is so direct and very intimate, in a way. The camera is almost taking part in the action itself. Most of the film is shot handheld, there’s very close distances, the camera feels and moves around the actors in a way as if it is a third person participating in all of it. That makes it really interesting.

I also felt that, when I talked to John [McTiernan], I said, ‘We need to do this all on location. No matter the location, we have to make this look real. Because if this film doesn’t look real, it’s going to be just like another action movie that we’ve seen so many of.’ And he totally supported that. And at that time, handheld was not used [very often] – it happened after, and was copied many times, but before that, it wasn’t really used. People didn’t think like that. It was such a big movie, you couldn’t do that. You had to treat it more like a regular stylized film like people had seen before. This was a moment in time where, basically, film was already on the verge of transitioning from analogue to digital. I always felt that this could be one of those last movies that still could really showcase all the advantages of analogue filmmaking.

John McTiernan has said he didn’t really storyboard this movie. Do you remember any conversations you had with him about specific shots in the film?

We didn’t storyboard much. The good thing is that John and I had such a great relationship, and to me, it’s always a matter of trust. When you storyboard the movie from beginning to end, I feel, as a DP, the movie has been made. So why would you get involved? Somebody else can do it. For me, you make the decisions on the set of how you’re going to do it. There’s no way in the world that a storyboard artist can imagine what an actor’s going to do, what the set will look like exactly, what the relationships between the characters will be. That’s how you have to film on the set, and the camera has to relate to that. You always have to see where everybody is at a given time in relationship to each other. Otherwise, you have all this confusion. I hate confusion in movies, where we have no clue where everybody is.

John gave me an incredible amount of freedom in that way. We talked about it before – every day, we drove to the set together and talked about the scene and what was important, what are the key elements, what we had to make come across and how tense it had to be, or was this scene a bit more relaxed. We talked more about the emotional and the suspense character of the scene, not so much, ‘Then a close-up of this, then a medium shot, then a wide.’ We never thought in those ways. Those were really great conversations in that regard between us, and really important.

One of the things I was surprised to learn about Die Hard was that a lot of it was essentially crafted on the go. The script wasn’t fully finished yet when shooting began. When did you know you were going to be able to use Fox Plaza for filming?

Actually, relatively late. We were looking at so many locations. The building itself is a character in the movie, so the character had to be seen and showcased. You needed the building to have character, and at the same time, we needed a building that was available [laughs] and was partially empty. So it was fantastic that, after all the locations we looked at, that was right next to us the whole time. What is so fantastic about that building, I think there were four or five stories occupied at the time, and many stories were still under construction. So we could use all of the floors that were not built yet and use them as set pieces.

Also, what is so nice about the building is that it had to be seen from far away. When Bruce sees it in the very beginning – when [limo driver Argyle] drives the car toward it, you only see it from a distance. As it comes in, the audience starts to get ideas about, ‘This building is special.’ Ultimately, it is. The whole story takes place in this one building, inside out, and what’s also important is what you’re seeing out of the building, you could see the outside. We weren’t in a studio looking at a blue screen or a green screen. It was always real. To make that real, the windows had to be extremely clear at night scenes and very filtered during the day time so there was a balance between inside and outside. We had to change those windows on two floors regularly. All the windows. It really felt like you were looking down and, there’s the city down there! That creates a lot of reality that is so much more important than cutting away and going to different locations.

Sort of along those same lines, Die Hard is regularly mentioned in terms of great actions movies that do an excellent job of establishing the geography of every scene. At every point, the audience is aware of where they are in the building. How were you able to execute that?

Yeah, that’s exactly right. Basically, as much as you can – for instance, the sequence when the helicopter comes in and lands on the roof – when the cameras are following and the actors inside go out to it, we know how high it is that they have to go. We’ve seen the staircases before. We really made an effort to showcase what floor we were on. We know where everything is, so that when those helicopters come in and we see those people come up from the floor down below – and that whole sequence is done in two and a half takes with 24 cameras all at once with no digital effects – everything is real. We’re on the roof and see the helicopter above, you can see it from below at the same time. There’s no cutting away and no feeling of ‘This was filmed two days later.’ No. It’s all there. You see the same people from both angles at the same time, which is so fantastic. For audiences, they know there’s a reality to this. It is basically like the camera is as caught in the building as the people are.

Can you talk about filming the explosions in this movie? There are a ton of them, and they all look very real. Were any shot on models or miniatures?

The only one that’s shot on miniature is the very top of the building. [laughs] Obviously, we couldn’t blow up the top of the building. But many other ones in the building are actually real explosions. For instance, when the police come in with that vehicle and [Hans Gruber’s henchmen are] shooting those rocket launchers at it, that is all real. We actually blew out all the windows on one particular floor. We did film those rocket launchers on a thin wire and torched that car. The audience knows the building so well that you can’t fake it anymore. The car goes up the real steps of the building, and the rocket comes right to that car and explodes, and all the windows blow out at the same time, too.

Unfortunately, that was a very scary undertaking because it was a brand new building. [laughs] What’s going to happen when all of the windows are blown out at the same time, and how to time it with the regular special effects guys? They did a fantastic job. It all happens almost casually, you know? We don’t make such a big thing of it. It happens, and then boom – we’re already going on to the next thing, so it’s not like Bridge on the River Kwai where it takes you twenty minutes to set it all up and then finally, finally, finally, it comes and the bridge explodes and the train goes down. No, this all happens much quicker and it’s much more real. That is a very unique approach to action movies.

I’ve done later movies with a lot of visual effects, but nothing is as good as the real effects. Anything you do with digital effects, in a split-second you can immediately see and feel that it’s fake. Also, for the actors, it isn’t possible to act accordingly to the quality of the effects. Quite often, nobody knows yet what they’re going to look like. You can say, ‘Oh, this will happen,’ but how can you respond to something that hasn’t been made yet and hasn’t been created? It’s impossible for actors to really become great in those movies. In this movie, the actors have to respond to the real thing. They are very close to those explosions. They’re on top of a real elevator going up and down!

You were talking about the exterior of the building and how it plays a character in the film, but in terms of the inside of the building, an office building can pretty easily become a pretty boring environment. How did you go about making it an exciting environment? I know you were responsible for a lot of the smoke we saw in the movie in those hallways and pipes, but what other tricks did you use?

That’s a really good point and a really good question. Offices usually use fluorescent lights in the ceiling, and that makes almost every room look the same. So what I did is, in those hidden ceiling pockets, I hid film lights. Very little ones that were all on digital dimmers, so I could set levels and create darkness and bright spots wherever I wanted it to be. The last thing I was trying to do was get this overall boring white light where every room looks the same. Quite often, for instance on the empty floors where there’s no lights yet, I could play with that. The fluorescents would lay on the floor in the frame as if they were just there to be installed the next day. So you could play with positions of lighting that you normally would not have if the building was completely already finished. So I could light it dramatically and play with it in any way.

I could change light settings during the shot, even. It’s really hard to have those big sets lit for everything at the same time, so quite often you have to dim and move things around while the camera pans from one to the other. That was a complicated set-up, but once you get used to it, the electricians all knew what to do. They realized very quickly how it had to work. Basically, all the lights are built into the set and the location, but you can never see them unless they’re hanging from the ceiling or broken or things like that. That’s how we were able to create an atmosphere that is more dramatic.

Was it in the script to have those burning pieces of paper floating around in the background during that big climactic showdown?

No, a lot of things weren’t in the script. [laughs] You asked how the script could change so much during the filming itself, and in a way, for this movie, it was really good. Because when Bruce Willis came into the set, he was available like three days before the movie started. He had just done the series Moonlighting and he wasn’t a known person for films yet. So everybody had to get to know him, and we had to see how he could play the character and what would work for him, and that was the same for all the characters in the movie. So the first week is always a bit of experimenting, and then you see how characters relate and how they talk. The dialogue had to be rewritten many, many times as we got to know the actors and felt what was write for them to say. Often you’ll read a script and have all those great lines, but if you hear them on the set, they’re so out of place that you have to change it.

So a lot of things were changed, and we were lucky having that building there that was still mostly empty, where we could do that. If all the sets are built and you have no more freedom, then it’s really, really hard. But we had this great opportunity to work and see what the tension between the two characters are. You don’t know until you see those two actors together. It’s still more or less the same story, but the intensity of the scenes have changed quite a bit.

The sequence where Hans Gruber falls at the end: I’ve heard there was a countdown for that and Alan Rickman was released at an unexpected time to get his real reaction as he fell. Is that true?

Yeah, and it was really difficult. When you see those shots happen, it’s always on blue screen, and we wanted – the most important reaction on a person’s face is the first second. If a person falls down away from camera in free-fall, it goes at such a high speed that you cannot get the focus right. That’s why nobody ever does it. So we had to design a system where there’s a computer that tries to set the focus to the rhythm of the speed he is falling, so we had to do a couple different tries for different people. It was a really difficult rig because nobody had ever done that, and it was a really big close-up. I don’t know if you remember, but it’s right in his face, right in his eyes. It’s also in slow motion, so anything that would be out of focus would be out of focus for a long time. The focus was so difficult and no focus puller could ever get it right. It’d be impossible. We were finally able to do it correctly.

And yes, you should never tell [an actor] exactly when [you’re going to drop them], because if you say, ‘We’re going to drop you at 3,’ then they’re always going to respond a fraction of a second early. Quite often it’s better to wait a little bit, do ‘1, 2, 3…’ and then the actor tends to get a little confused, and then you drop, and then you get the best reaction. [laughs]

The thing about the focus pulling is amazing. I’ve never even thought about that before, but of course that must have been incredibly difficult to do.

It is, because it goes so fast. It starts maybe two feet away from the lens, and then he goes from two feet to seventy in no time. So if you want every little frame of that, hundreds of frames, to be in focus, it’s like, an impossible task. It was basically something that was invented for the military, I think. They were just experimenting with that, a little company in the Valley. They had never done it for film either, they had done it for some kind of video shoot for the military. But they adapted it for us, and ultimately it worked.

Did you do a lot of testing and prep with that before you got Alan Rickman hooked up? How many takes did he do?

I think he did three takes. Sometimes, the first take is often a surprised reaction. But we didn’t want just surprise. It had to be the realization that he was going to die. You have to give the actor…in a case like this, it’s almost better to have them make sure that when he falls, he’s going to be safe when he hits the bottom. Because he’s going to fall on a big airbag way down there. Most actors are so worried about all of those stunts, and rightfully so, and they should be done safely. Once they know it’s safe, they can act. But then you still have to time it right. So you still have to surprise him when it really goes.

What did you learn making this movie that you brought with you in the rest of your career?

I think flexibility is the most important thing. It’s not a thing that’s high on the list of possibilities on those big budget movies. Flexibility? That’s the last thing they want, because they want everything to go according to plan. But certain things had never been done before, and we did things where while we were shooting, we quickly did a tryout of a scene somewhere else to make sure that the next day, that effect might work. We were totally prepared to move very quickly from the 43rd floor to the 39th floor, so we could move very fast.

Flexibility – if things don’t work, immediately thinking of another way to solve it. If it doesn’t work, don’t just accept it. Find a way to get it right and make it meaningful and dramatic and suspenseful. That’s really key. Never cave in. Make sure you get it right.

Why do you think this movie still holds up so well 30 years later?

I think the viewer is pulled into the movie, basically, because it’s at a relatively high pace and it moves all the time. And it moves in a way where they are seeing something new and they have to pay attention. Quite often the audience will just sit and watch and don’t participate in the movie, and I really like very much if the audience has to make an effort to really go along with the movie, with the storytelling, with the way it’s visually told. I think that’s really, really important, especially for today’s audiences. Let them not only enjoy it, but let them make an effort to follow the story and feel the tension. Every shot in this movie has a certain suspense and tension. [When I saw it recently], I was surprised how it’s still such a good movie! It still holds up so well. It still feels fresh, which is very hard to say of movies that are thirty years old.

What is the thing that you most proud of regarding Die Hard?

What I really liked about it was that it was never about making beautiful shots. It was always about making shots that are dramatically important. Any cinematographer knows that it’s great to make beautiful shots, but it’s also a little boring. Beautiful shots tend to take you away from the story, it distracts you. I much more like dramatic shots, where things are darker or you can’t see very well or there are flares in it. All those flares in the movie, too, those are on purpose, by the way. Because it’s real – that’s how it would happen. When things happen quickly, you have flares. That’s like what we have in real life, too. When you’re at night and you see police cars coming, all you see are the flashing lights and the flares, you can’t see everything correctly. That tension, that drama, is not about beauty. It’s really about visual urgency, and that visual urgency makes this movie such a great picture.

Continue Reading Die Hard 30th Anniversary Interviews >>

The post ‘Die Hard’ 30th Anniversary: The Cast and Crew Reflect on the Making of an Action Classic [Interview] appeared first on /Film.

we need your feedback